"Trauma is rare. Resilience is not."

So says Dr. George Bonnano of Columbia University. In a recent YouTube interview, he argues that violent or terrifying experiences, while certainly upsetting in the short term, mostly do not lead to lasting mental harm. In the wake of horrors, he says, resilience is the norm, and PTSD is rare. His research asks, "Why?"

The comment section has loud, angry answers for him. Turns out, people who suffer from trauma-related distress don't appreciate being told that most of us just get over it. "Survival mode isn't resilience," they fume. "You know nothing, Dr. B."

In this issue of Mindfalls, we dive into the Big T-little t debates. Are Dr. Bonnano's views insightful or obtuse? Has our society become too trauma-informed? Is resilience something we can learn? Does the body really keep the score? And how did the shell-shocked veterans of WWI transform the way the world thinks about mental illness?

by Jocelyn Davis

“Bad experiences in my past caused my mental illness. It’s called complex post-traumatic stress disorder.”

Had you spoken those words anywhere in the Western world before 1980, your hearers might have taken them as further evidence of your insanity.

Trauma-informed approaches to mental illness are a recent development in the grand scheme of things. To the physicians of ancient Greece and Rome, madness, like most other diseases, came from imbalanced bodily humors. In medieval Christendom, your sins had angered God and given demons a soft target. For the early Victorians, the problem was your degenerate behavior, probably sexual, which had rotted your body and mind. The late Victorians were less judgmental; for them, the culprit was germ infection, pernicious hormones, or weak nerves resulting from unhealthy habits or simple misfortune.

There’s a threefold thread running through these historical views: mental illness was 1) certainly innate, 2) perhaps the sufferer’s fault, and 3) probably permanent—though as to the last point, some relief might come from “treatments” ranging from comatose sleep (maintained with heavy doses of barbiturates) to focal-sepsis surgery (removal of the tonsils, teeth, colon, or anything else that might be “poisoning” the brain) to multiple seizures (induced with insulin, convulsant drugs, or electricity) to the most lauded psychiatric procedure of the early 20th century: the mutilation of the brain’s frontal lobe, aka lobotomy.

Jocelyn Davis writes books about leadership, history and literature, and mental health. Learn more at JocelynRDavis.com.

TOP TIPS FOR RESILIENCE IN THE FACE OF BREAKDOWN

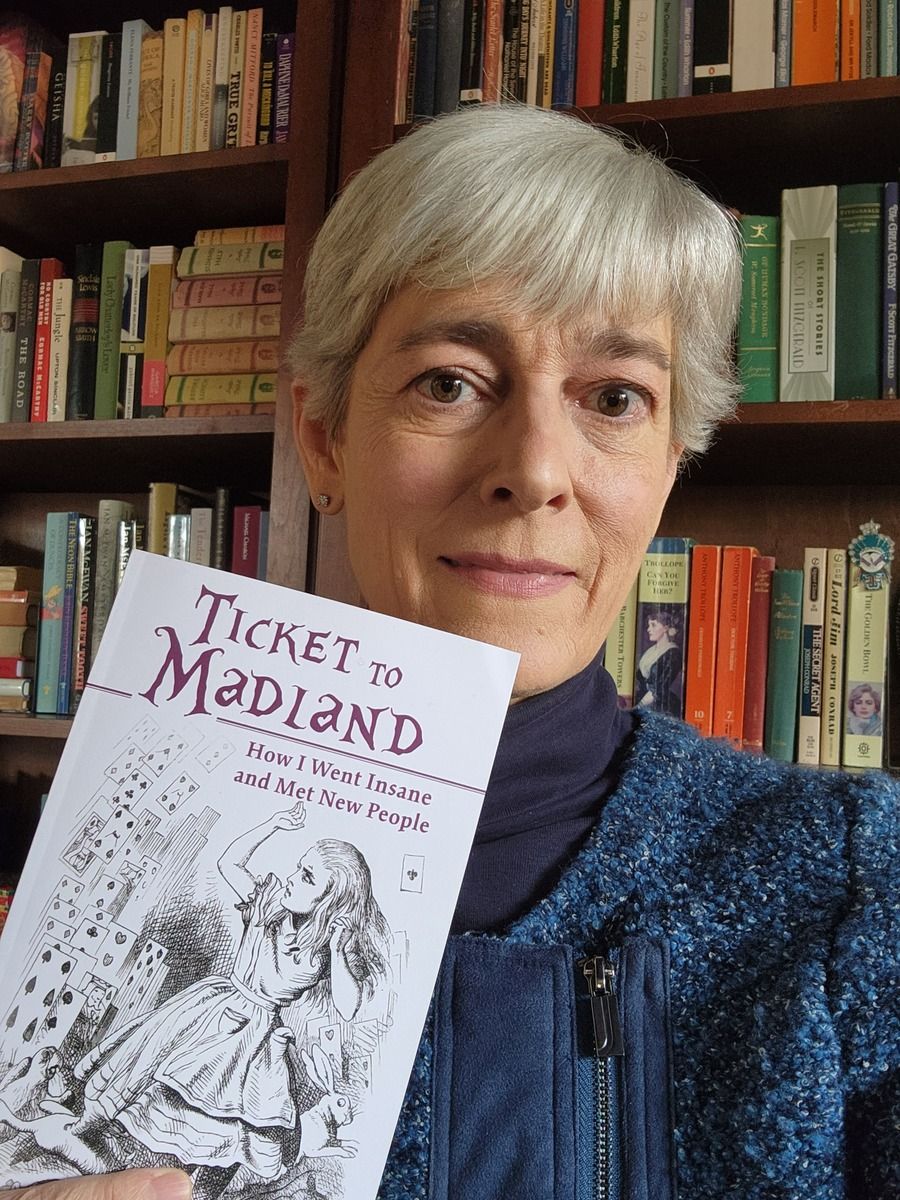

Ticket to Madland is the fearsome yet funny memoir of my trek through a mind-body illness involving vertigo, insomnia, anxiety, and a host of other wacky symptoms, culminating with two weeks in a locked psychiatric ward. (Spoiler: I recovered.)

In the book’s epilogue, I share four lessons learned. Here are the first two. –Jocelyn Davis

***

The first [lesson], I’m sorry to say, is that when you’re going insane it’s advisable to have plenty of resources. Money for sure, but on top of money you’ll want good insurance, a stable home life, sympathetic friends, and a supportive employer. You’ll also want a healthy body, familiarity with bureaucracy, and an education that puts you at ease with complex medical information—plus the sort of demeanor, not to mention skin color, that encourages doctors to take you seriously and treat you with a modicum of respect. In other words: privilege. Nearly every Madlander I encountered lacked privilege, at least compared to me. Did they make it through nevertheless? I don’t know. I think of them often: the Carpenter, the Fawn Girls, Savvy Alicia, Emotional Teresa (“I feel your dizziness!”), Kathy the Mock Turtle, Jackie the Jabberwock, Miranda the Gryphon (“That is bullshit!”), Coloring Girl Lindsey, Cast-foot Sam, Mad Hatter Joe (“Do ya wanna use the phone?”) and of course, dear disconnected Tessa (“I made this for you so maybe you won’t cry anymore”). I think of them all and wonder how they’re doing.

Me, I’m doing well. I’m still on the Zoloft pills and the estradiol patch, and I take progesterone and melatonin every night, 90 minutes before my boringly regular bedtime as advised by Dr. Taylor. I weaned off the clonazepam over eighteen months, slowly and without difficulty, cutting then shaving down the pink tablets until I was taking a mouse crumb a day, then none. I still keep a small stash in case of disaster, but the bottle on the third shelf of the linen closet remains full … Sleep is good: when you count naps, I get a solid eight hours in each twenty-four.

Yes. I am very, very lucky.

Cultivating a Trauma-Informed Behavioral Health Workforce

Creating a trauma-informed behavioral health workforce is essential for both client care and staff well-being. With trauma widespread and burnout high among behavioral health professionals, organizations like NYPCC prioritize safety, trust, staff support, trauma-informed supervision, wellness resources, and thoughtful workforce development. This holistic approach strengthens resilience, reduces turnover, and improves the quality of care for clients and communities.

Trauma is a leading mental health challenge that tests both mind and body

Millions struggle with mental health challenges, and trauma is one of the most significant contributors. Dr. Steven Berkowitz of the University of Colorado explains that trauma is a person’s reaction to a stressful event, not the event itself, and can lead to a wide range of issues beyond PTSD, including anxiety, depression, and substance use disorders. Treatment often involves cognitive therapies, medications, grounding techniques, stress-reduction strategies, and family support. Because trauma and chronic stress can impact nearly every system of the body and increase long-term health risks, Berkowitz emphasizes individualized care, early intervention, and building more resilient, supportive communities—not simply treating symptoms after they emerge.

Desperate Remedies: Society's Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness (book). In this erudite yet super-engaging history, author Andrew Scull unpacks how insanity has been conceptualized, treated, and mistreated from ancient times to today. Chapter 14, "War," tells how post-traumatic stress disorders emerged from 20th century battlefields and how they transformed the way the world thinks about madness.

PTSD vs CPTSD (video). If you want a short, clear primer on the two main types of post-traumatic stress disorder and how they differ, check out this video by Dr. Scott Giacomucci of the Phoenix Trauma Center.

Tell Me Why It Hurts (article). NY Magazine's Danielle Carr explains how Bessel van der Kolk's once-controversial theory of trauma first took over psychology, then morphed into the recovered memory movement, and finally became the dominant way many people make sense of their lives.

The Memory Hole (podcast). A fascinating, disturbing look at the 1990s mental health crisis known as the Recovered Memory Movement--featuring sketchy therapists, multiple personalities, Satanic panics, and much more.

The Mindfalls newsletter is for informational purposes and is not a substitute for professional help. If you are having a mental health crisis, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, reach out to your doctor, or go to the nearest emergency room.