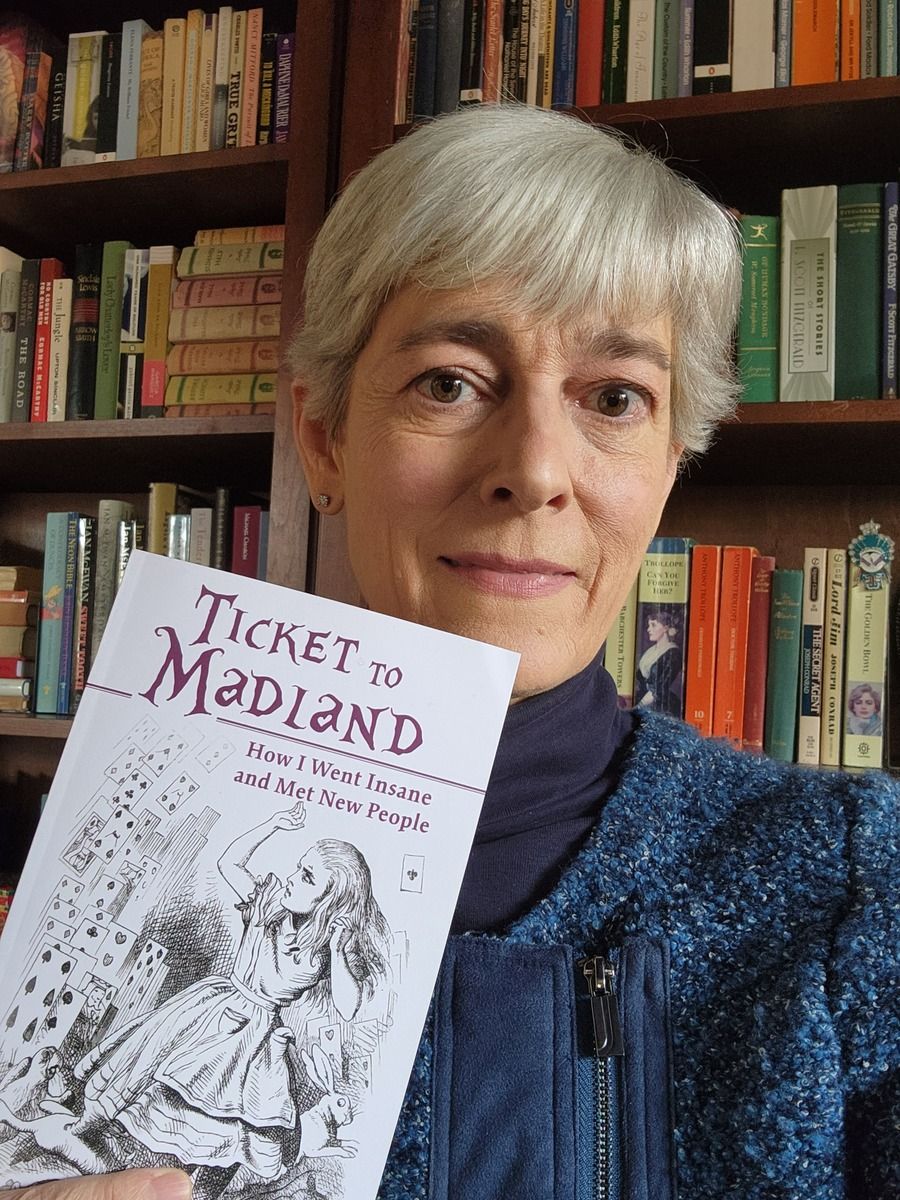

Ticket to Madland is the harrowing yet humorous story of my trek through a bizarre brain-body illness, culminating with two weeks in a locked psych ward. “Reads like a medical thriller,” says one reviewer. (Spoiler: I recovered.)

The scene below takes place in October 2020: nine months into the Covid pandemic, eleven weeks into my ordeal. I’ve secured an appointment with an eminent neurologist who is going to underdiagnose me. Although he was kind of a jerk, I must admit that my approach didn’t help. I wish I could go back and share these tips [JK: please link to the Goldilocks article] with my former self. –Jocelyn Davis

***

“I want you to remember these three words: green, Denver, horse. Repeat them back to me.”

“Green, Denver, horse.”

“Good. Now, spell ‘world’ backward.”

“D … um … d, l …” Perched on the end of the exam table in Dr. Andersen’s office deep in the labyrinth of Mountain Medical Center, I struggled to picture the word world backward. World is w, o, r, l, d, now reverse it, c’mon, it’s only one syllable. “D, l … um … r, o, w.”

“Now repeat the three words I asked you to remember.”

“Green, Denver, horse.” (Did I pass? Did I pass?)

Dr. Ortega, upon prescribing the Lexapro, had given me names of a few neurologists. Covid was raging in Santa Fe, making it nearly impossible to get in to see any doctor, let alone a specialist, but when I called Mountain Medical to inquire about Dr. Andersen, they astonished me by saying he had an opening the next day at ten a.m. I booked the appointment.

The facility was fancier than most, with an airy, high-ceilinged lobby guarded by receptionists in germ-safe glass booths and furnished with purple-and-green striped couches that almost matched my purple blazer and green glass earrings. (Well-groomed!) Although the buzzing anxiety was now near-constant, I was still able to hide it well enough, and when the ponytailed nurse came to the waiting area to fetch me, I rose, dusted off my purple shoulders, adjusted my mask, and followed her into the labyrinth chatting cordially. The interior was 21st century high-tech, brimming with white, chrome, and beige, like an IKEA.

Nurse Ponytail spent a good fifteen minutes recording my history and symptoms. She also asked me a set of questions about depression. I didn’t like having to answer eight of the ten with “yes” or “almost always,” but I was determined to be truthful. One question to which I answered “no” was Do you have a suicide plan? This, I would later learn, is the main question the pros use in order to gauge depression’s severity: if suicidal ideation is a red flag, having a plan is thought to be a much redder flag, a sign you’re much closer to doing the deed. The other outlier question was Do you feel guilty about how your depression is affecting those close to you? I thought about that for a moment: Did I feel guilty? “No, I can’t say I feel guilty,” I said as Nurse Ponytail typed away, “but I know this whole situation is making things very tough on my husband. Really, I just want to get better.” She thanked me and said the doctor would be in shortly.

Dr. Andersen—over six feet, portly, with lank gray hair—entered the room with a Scandinavian-accented “Good morning!” and dropped himself into the desk chair, the springs of which groaned as he leaned back with knees wide. He clicked his ballpoint pen and held it poised above his clipboard. “Right, Jocelyn, tell me what’s going on.”

I was ready. I’d been referring to my notes during Nurse Ponytail’s interview; now I consulted them again. “OK, so, since July sixteenth I’ve had this weird bouncy vertigo, plus nerve pain, insomnia, anxiety, and some other symptoms. This is my second major episode. The vertigo has been diagnosed as this thing called Mal de Débarquement Syndrome, and—”

“Don’t look at your notes!”

I jumped. “Sorry, what?”

“Put away your notes!” His booming voice pounded my eardrums.

“Oh, sorry, but I need the notes to help me remember. It’s hard for me to focus—”

“Put AWAY the notes. Just tell me how it FEELS.”

I stared at him as I considered walking out. Jesus, this guy is an ass. Better humor him. With an effort, I kept my eyes on his masked face. “OK, well, it feels like I’m on a boat.”

“How often do you feel like this?”

“All the time. Except when I’m driving or sitting in a rocking chair.”

He scribbled on the chart. “What else?”

“Well, there’s this pain, right now it’s all over my scalp—”

“What does it feel like?”

“Like a cross between a sunburn and a bruise. Sometimes it’s itchy or tingly—”

“How often do you get this pain?”

My eyes dropped to the paper in my lap. I wrenched them back up. “I think this is about the fifth time it’s been this bad.”

“And what exactly does it feel like?”

On we went, back and forth, with him quizzing me about the exact how, when, and where and me trying to answer sans notes. I stressed my sleep problems: “I wake up after a few hours.”

“Why do you wake up?”

“I don’t know.”

“You don’t know why?”

“No, I don’t know why.” If we knew why, you numpty, we wouldn’t be here!

I considered saying more about the mood problems and decided not to, figuring that soon he would review what Nurse Ponytail had typed into the computer and see the depression questionnaire. But he never did. He seemed to be inspecting me closely, and after ten minutes of interrogation he put the chart aside, waved his hand at me like a museum tour guide indicating an artwork of negligible interest, and remarked: “You seem relaxed.”

I had no idea what to say to that. We are the very opposite of relaxed, my dear Caterpillar.

“OK, come up here on the table and let’s have a look.”

He whizzed through a series of neurological tests: follow finger, squeeze hand, whack knee with rubber mallet, etcetera, wrapping up with the memory challenge: green, Denver, horse. He had me return to the chair and asked if I’d ever had migraine headaches before. “No,” I said.

“What about female relatives?” he asked.

“Nope.”

“Are you sure? Your mother, sister, an aunt maybe?”

“No, no one.” Yes we know what female relatives are, and none of them has migraines.

“Hmm. Well, you don’t have a brain tumor; tumors don’t act like that. This is functional.”

“Functional?”

“Not structural. And according to you, you’ve had this before and you got over it. So you’ll probably get over it again.”

“Right, but this time it’s so much worse.” Should I tell him to look at the depression questionnaire? That I think about killing myself? How do I convey suffering without conveying hysteria? “I mean … I feel really, really bad. Could it be a virus?”

“No. I believe you have vestibular migraine.”

“Oh! Huh. I’ve read about that, and I did wonder—”

“Yes. I’m going to give you nortriptyline. It’s an antidepressant used for migraines, and it will also help you sleep. It’s quite sedating. No side effects, except maybe a little blurry vision.” He screwed his balled fists into his eyes by way of demonstration: Vision. Blurry.

“What about the Lexapro I’m already on?” And by the way isn’t nortriptyline similar to amitriptyline, which is that stuff the Knave of Hearts said gave him hallucinations?

“No, Lexapro is good if, like, somebody in your family has died and you’re feeling sad. Nortriptyline is better for this.”

“Yes, but—”

“Stop the Lexapro. Nortriptyline will be better. 25 milligrams to start. If it’s not enough, call me and I’ll give you a higher dose. I’ll see you again in a month.”

The early October sunshine was warm as I crossed the parking lot, clutching the discharge papers with my diagnosis noted in the upper right corner: “Migraine Variants.” Green, Denver, horse. Green, Denver, horse. I drove to CVS and picked up the new meds.

***

Ticket to Madland: How I Went Insane and Met New People is available on Amazon and wherever books are sold.