Happy New Year from Jocelyn and Kelly! Mindfalls is taking a holiday break and will be back on January 14th. In the meantime, three things:

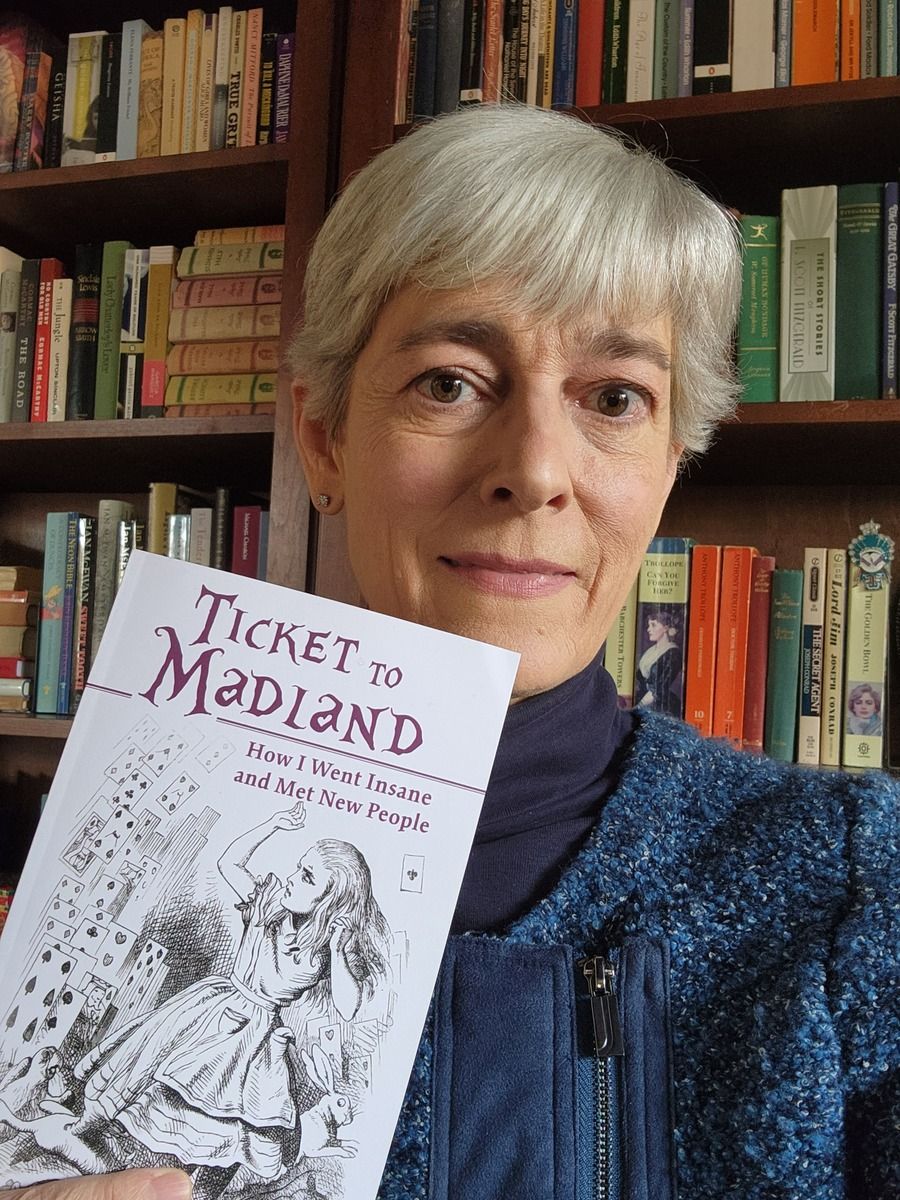

Talk to us: Let us know what mental health topics you’d like us to cover in 2026. Simply reply to this email with your thoughts. (Replies go directly to Jocelyn’s inbox.) We’ll publish all the suggestions and do a poll. A free copy of Ticket to Madland goes to the winner.

Catch up on previous issues of the Mindfalls newsletter here. So far, we’ve done issues on under- and over-diagnosis (let’s avoid both), complex trauma (can we get over it?) and ways to go beyond mental health first aid to offer substantial support (hint: it’s not about empathy). Scroll down to the bottom of the Subscribe page to find the full newsletters. And please do help us out by passing them along to your friends. Sharing is caring :)

Be the first to read the first three pages of the NEW BOOK, below. We have a draft of Chapter 1, but we’ll be writing and pitching and editing and marketing and generally tearing our hair out for the next 18 months at least, so this is a truly sneaky sneak preview just for you wonderful subscribers. (Acquisitions Editors: We have a full proposal that we’re eager to share.) Here goes …

Jocelyn and friends

Kelly and friend

UNLOOPED: The Sane Person’s Guide to Mental Breakdown and Recovery

© Jocelyn Davis and Kelly Kinnebrew, 2026

Chapter 1: Breakdowns Revisited

They used to call them nervous breakdowns.

There you were, a busy competent sane person with a job, a family, places to be, goals to pursue, a good head on your shoulders. Then a terrible thing happened, or a bunch of bothersome things happened, or maybe nothing at all happened, and that good head of yours decided the best next step was to fling itself into a sinkhole of anguish and despair, dragging you along with it. Perhaps you didn’t realize you were in the sinkhole, not at first, but your close friends did, and they worried about you: “You OK?” “What’s wrong?” “Can I help?”

“I’m fine,” you said, pulling on your Normal Human mask and bicycling your legs faster in the murky, gritty slosh. “Got a lot going on. I’m fine, really.”

“You sure? Maybe you should talk to someone.”

“I just need some sleep.” (Hard to sleep when you’re trying not to drown.)

After a while, you decided to take your friends’ suggestion. You strapped your Normal Human mask tight to your face, took a deep breath, and … made appointments, filled out forms, perched on exam tables, lay in scanners, found a therapist, ditched the therapist, found another therapist, unpacked your trauma, organized your pills, downloaded meditation apps, and ate fiber. You sought out all the Help, and you weren’t much helped, but you kept going, and as you went along you wondered why the Help was so difficult to access, so tentative in its advice, so quick to usher you out of its office with a prescription for an antidepressant and a directive to get more exercise. Eventually you started glancing around, furtively, for the string to pull to make the Acme safe drop from the sky, thereby squashing you and the problem. Not that you wanted to die … no, you didn’t really want to die. You simply felt too awful to live.

Throughout most of the 20th century, nervous breakdown was a common all-purpose term for a sudden onset of mental dysfunction in a typically well-functioning person. Anyone could have one, and lots of people did. In the 1980s, the term fell out of fashion; for reasons we’ll discuss in chapter 3, clinicians and patients alike began to prefer that mental problems be classed as distinct diseases, each with its own symptoms, its own treatments, and—very important in the United States—its own insurance codes. According to this new medical paradigm, sometimes called the disease model, a patient might “have” depression. Or an anxiety disorder. Or bulimia, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, OCD, PTSD, ADHD, or one of a hundred other D’s that doctors were trained to address. Behavioral problems, too, were given disease-like labels: problem drinkers now had alcohol use disorder, unruly children had oppositional defiant disorder, jerks had narcissistic personality disorder. Issued in 1994, the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, psychiatry’s bible, contained 297 diagnoses. The nervous breakdown was by then regarded as a quaint relic of a time before everyone knew that mental illnesses were exactly like physical illnesses: precisely classifiable, probably chemical, and the job of medical professionals to name, evaluate, and treat.

Huge advances, everyone thought, were around the corner. Yet today, psychiatric medicine can claim no victory over mental illness—not compared with what cardiac medicine, say, has done for heart attacks. Nor can we hand a trophy to a second discipline, behavioral health, which takes prosocial conduct (aka “not using”) as its key metric. A third model, wellness, has also been disappointing. Rooted in the evidence-free theories of Freud, fertilized by the new-age movements of the 1970s, wellness was and is sustained by its consumers: people with time and money to spend on woodsy retreats, holistic regimens, and for the truly dedicated, years of talk therapy. Wellness’s results, taken as a whole, are uncertain at best.

To be sure, all three paradigms—psychiatric medicine, behavioral health, and wellness—can point to successes. Many of us swear by our Zoloft, our AA meetings, our yoga practice, our beloved Jungian therapist. Nevertheless, industry forecasts tell a sobering story: the health research firm Longevity, for example, reports that “the global Anxiety Disorders and Depression Treatment Market” was valued at $20.51 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $34.31 billion by 2033.[i] While investors celebrate “robust growth” and analysts attribute that robust growth to “rising mental health awareness” along with “the development of innovative pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapies,” we can’t help proposing a less upbeat interpretation of the data: Despite a century of strenuous efforts across multiple fields, the worldwide incidence of mental illness looks to be increasing by about 5 percent per year.

This is disheartening news, especially when you consider the money that’s been poured into the search for remedies. Thomas Insel, looking back on his thirteen years as head of the National Institute of Mental Health, observed: “I realize that while I think I succeeded in getting lots of really cool papers published by cool scientists at fairly large cost—I think $20 billion—I don’t think we moved the needle in reducing suicide, reducing hospitalizations, or improving recovery for the tens of millions of people who have mental illness.”[ii]

So what do you do? When you’re flailing in the sinkhole, mask slipping, strength fading, and you realize no one is coming to save you, how do you save yourself? When all the talk, tests, and treatments feel like cinderblocks lashed to your ankles, how do you find the power to stay afloat, let alone swim ashore? When the professional help isn’t helping, when the working theories aren’t working, where do you turn for answers?

We, Kelly and Jocelyn, know a lot about that murky, gritty sinkhole, both from our personal experience and from the many other survivors we’ve interviewed. We say: It’s time to revisit the nervous breakdown. Let’s examine the phenomenon with fresh eyes and ears, focusing on real people’s stories rather than on the expert opinions inscribed in the now-more-than-500 diagnostic categories and subcategories of the DSM. Those real-life stories, if we listen not just to empathize but to learn, will lead us to a new account of mental illness, simpler and better than the narratives the diploma-displayers have been pushing for the past century. And for those of you now treading water in the hole, or teetering on the edge, or back on solid ground praying to stay there, this new account will offer eight supports:

1. Assurance that you’re not alone;

2. Knowledge of the mental health system’s structures, resources, and traps;

3. Insight into your particular type of breakdown;

4. Strategies for coping with that type;

5. Trust in your Core Self to lead when your mind can’t;

6. Courage to move and change;

7. Patience to accept and wait; and

8. Faith that you’ll make it through.

Ready to go? Let’s start with a story about a man with a stressful job …

[i] Oberoi, Aaina, “Anxiety Disorders and Depression Treatment Market Size and Forecast (2025-2033),” Longevity, Dec 17, 2025. url: https://vocal.media/longevity/anxiety-disorders-and-depression-treatment-market-size-and-forecast-2025-2033-vu6le0pq4

[ii] Scull, Andrew, Desperate Remedies: Psychiatry’s Turbulent Quest to Cure Mental Illness,” Cambridge, Mass: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2022, p. 357.